I confess. I’m smitten.

People who know me well are (all too) aware that for the past several years I’ve been obsessively plugging away at a research project.

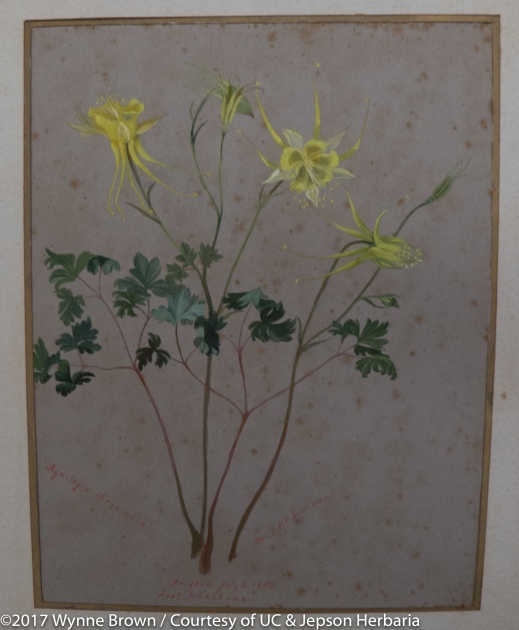

Photos by Wynne Brown; originals at the University and Jepson Herbaria Archives, University of California, Berkeley

I’m now going public with my obsession.

I’m so smitten that the voice of this plucky woman has pulled me — not once or twice, but three times — all the way from Tucson to Berkeley. That’s where her letters are stored, in the University of California and Jepson Herbaria archives. And that’s where I’ve photographed her century-old correspondence, all 1,200 pages of it. With my iPhone.

I’m now (slowly) transcribing those pages.

But there’s more to this story than just words…

Sara Plummer Lemmon wasn’t only an observant, prolific, and engaging correspondent: According to one source at the time, her gift for drawing in the field combined with her thirst for scientific knowledge made her “one of the most accurate painters of nature in the State.”

Tragically, most of her illustrations were lost, possibly in one of the fires that accompanied the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Fortunately, two boxes of her artwork had been stored in Hawaii and were donated recently to the Berkeley archives. Times being what they are, the university lacked the funds to examine and evaluate the extremely fragile works, which are all on paper.

So, with the help of generous donors (thank you, again!), I hired a local conservator whose efforts revealed 276 watercolors and field sketches. Which of course I also photographed.

Here are two of them – both signed and dated, and painted by Sara in the field, in Southern Arizona’s Huachuaca Mountains in the fall of 1882.

More details on her artwork (those brown spots are called “foxing” and have a fascinating story all of their own) to come in a future post.

Most recently, I’ve submitted a nonfiction book proposal to various agents, along with three publishers. Here’s how I’ve described the book:

“LIKE DEATH TO BE IDLE: Sara Plummer Lemmon, 19th-Century Artist, Scientist, and Explorer, blends popular science, history, and biography. It uses Sara’s exquisite artwork and lively correspondence to bring another female ‘Hidden Figure’ of science to general readers. Her story is one of tenacity and grit, of Western exploration, pioneer women, Apache warfare, the Civil War—and romance.”

Who IS this woman? and why would anyone in 2017 care about her?

Sara Plummer was born in Maine in 1836 and educated in Massachusetts. She then taught art and “calisthenics” (known to us as gym) in New York City. In 1870 her story becomes that of the early American West: At 33, driven by poor health in the East Coast climate, she relocated—all alone—to Santa Barbara. There she taught herself botany and established the community’s first library in the back room of a stationery store. In 1880, she married John Lemmon, a Civil War veteran and renowned botanist, and moved to Oakland; the couple spent the rest of their lives collecting and describing hundreds of new trees and flowers, all illustrated by Sara. Her letters document their often-harrowing trips through the unsettled West, including the Arizona Territory and northern Mexico. By then she was an acknowledged botanical expert in her own right: She was the second woman allowed in the California Academy of Sciences—and the first to be invited to speak to the group.

In addition to being an artist, scientist, and writer, Sara somehow also contributed her time to journalism, women’s suffrage, and forest conservation.

I believe Sara’s story is a universal one of determination, resilience, and courage—and is as relevant to our nation today as it was in the 1880s.

And I believe it deserves to be heard.

Stay tuned …